|

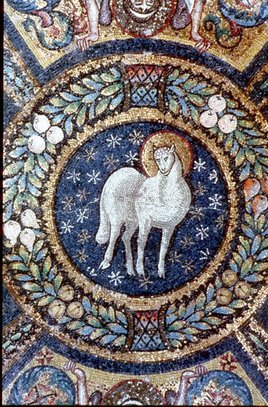

The Lenten Season is officially upon us, embodied by a spirit of reflection and repentance culminating in the Celebration of Easter on April 16th. As there is an undeniable influence of Christian theology on the history of art, every Sunday of Lent we will explore art with distinctly Christian themes in a methodology known as visual theology. On this Good Friday, we examine the somber subject of Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God. "Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!" - John 1:29 (NIV) Painted during the heights of the Spanish Catholic Reformation, Francisco de Zurbarán's Agnus Dei is shocking in its simplicity of a lone Christian icon. The religious art of the Baroque period is frequently characterized by the dramatic works of Bernini, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Rubens. Zurbarán, however, abandons drama for subtle poignancy. Set against a black backdrop and laying upon a gray table, a live merino lamb is tied and bound in a sacrificial position; its legs are thrust into the foreground and its eyes avert our gaze. There is no other iconography only the heartbreaking sense that the melancholy lamb is resigned to its sad fate. While technically there is no iconography to suggest the allegory of Christ as the 'Lamb of God', the image was widespread throughout Christian imagery, especially in (predominantly) Catholic Spain. In addition, the position of the lamb itself recalls that of Stefano Maderno's haunting Martyrdom of Saint Cecelia sculpted 30 years prior. The direct correlation between the two figural positions serves to reinforce the sacrificial nature of the lamb's existence. The subject was well received by the people of Seville, Spain. Once Diego Velazquez left for the royal courts, Zurbarán became the City's official painter by 1629. Between 1631-40 he painted five versions of Agnus Dei for private patrons, with slight iconographic variants. Yet, it is the unadorned version that is considered the finest of the five.[i] Its poignancy highlighted through Zurbarán's ability to "concentrate the viewer's attention on a lamb that seems to meekly accept its fatal destiny." [ii] There is nothing to detract the viewer from the lamb's sacrifice. No halo, no lilies. Only life--a life that will be given to pardon the sins of the world. Agnus Dei is often treated as a still-life, a genre of painting frequently associated with food or perishables acting as a memento mori. The lamb is indeed edible and its life coming to an end. Unlike most still-lifes, however, the process of death and/or decay is not shown for this is the food of life. The symbolism is two-fold. The unblemished sacrifice refers to the lamb of Passover, whose blood saved the Jews in Egypt and Christ, the Lamb of God, whose blood redeemed the sins all mankind. Zurbarán utilizes his artistic skill in rendering the texture of the lamb's wool with a technical subtlety that further underscores this is a lamb without blemish. This indeed is the Agnus Dei who is acting as the pardon for our sins. It is also his body we are consuming in an act of transubstantiation during the holy rite of Communion, a moment first celebrated at the Last Supper as described in the Book of Matthew: "While they were eating, Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, 'Take and eat; this is my body.' Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, 'Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.'" [iii] Zurbarán forces the viewer to confront the paradoxical nature of Christ Biblically and as seen art historically. He is both the Good Shepherd and the lamb, divine and humble, the triumphant and the slain. As a relatively new religion, early Christian imagery favored more Johannine depictions of the Agnus Dei. Their god could not be shown as meek and humble, but rather as a glorious deity who conquered death. By the 13th century, Franciscan theology created a shift in Christian imagery. Gone was the triumphant Lamb of Revelation, now replaced by a meek animal, humbly offering itself to humanity. This is the Lamb of God we encounter in Zurbarán's poignant masterpiece. Agnus Dei enables us to "recognize in this wooly lamb, bound and patiently waiting on a slab for the butcher's knife, the Saviour on the altar, the Son of Man suffering in atonement for our sins."[iv] And it is this recognition of Christ's complete and sorrowful surrender to death so that we shall live that makes Zurbarán's Agnus Dei one of the most moving of all images in Christianity. "He [Jesus] knelt down and began to pray, saying, “Father, if You are willing, remove this cup from Me; yet not My will, but Yours be done.” -Luke 22: 41-42 i The canvas has wax seals bearing Ferdinand VII's coat of arms. The painting originally belonged to the family of Marquis del Socorro. The state acquired it for the Prado in 1986.

ii Museo del Prado iii Matthew 26:26-28 (NIV) iv Neil MacGregor, Seeing Salvation, p.73.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorScholar. Student. Unadulterated lover of all art forms. Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed